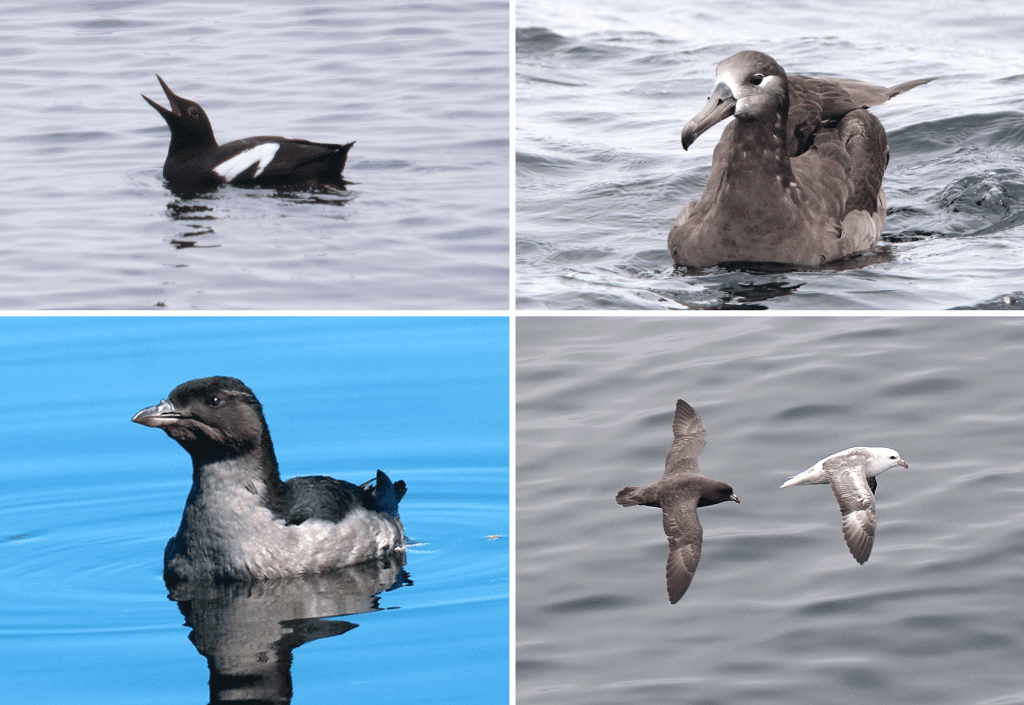

When you’re a birder at sea, there’s a host of charismatic, winged dinosaurs you expect to spot as you navigate away from the coast and into the open ocean. On departure from port, you listen for whistling pigeon guillemots and keep an eye out for rhinoceros auklets disguised as blurry blobs bobbing in the waves. A black-footed albatross soaring overhead is a good indicator that you’ve left the coast behind. Far into the Pacific Ocean, northern fulmars appear as regularly as robins and jays back on land.

Every so often, a bird that is obviously not a seabird – conspicuously lacking in webbed feet or wings made for soaring – can be found on an ocean-faring ship. These unexpected visitors often appear haggard and frumpy as they cling on to whatever their feet can grab: slick railings, lines of rope, and even the metal rungs of a stowed gangway. They may be victims of strong winds, blown out to sea during their migration or as a result of their own faulty biological navigation systems. Amid the soaring albatrosses, fulmars, and petrels, a forest-dwelling sparrow might seem like an imposter, lost and entirely out of its element.

Joining the crew of NOAA Ocean Exploration’s Seascape Alaska 1: Aleutian Deepwater Mapping expedition as the office’s science communication Knauss Fellow, I felt like how a wayward sparrow might appear on a ship: an imposter, wholly unfit for life on the ocean and unsure where my niche would be. My background is not in ocean exploration, and before this expedition, I had never spent more than eight hours at sea. I’m more of a coastal soul, used to working in salt marshes and bays, familiar with the smell of sulfuric wetlands and the sound of ospreys calling. Working on a ship off the continental shelf was an entirely new experience for me, and although I was excited and looked forward to it, I felt anxiety starting to creep in as the trip approached.

When I stepped onto NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer – the only federal vessel dedicated to ocean exploration – for the first time, I wondered if my inexperience made me stick out like a sore thumb. All around me, seasoned scientists lobbed words that I knew I was supposed to know but that didn’t register: “sub-bottom profiler,” “EM304 multibeam sonar,” and “VSAT,” to name a few. Instantly, the imposter syndrome I’ve been battling throughout my scientific career made my stomach swim with nerves. I was eager to voyage through the Gulf of Alaska and visit the Aleutian Islands. Still, I was also worried about fitting in, producing good science communication content, and not falling overboard from Okeanos Explorer—like the fox sparrow that visited the ship in the first few days of our expedition, I was clinging on to everything.

I’ve run this race before: I’ll start a new position, see how competent everyone else is, and immediately question my abilities in comparison. Imposter syndrome is not uncommon (though it disproportionately affects women and racially, ethically, and religiously marginalized groups), and it’s natural that some anxiety may arise when faced with unfamiliar territory. But doubting my skills could have anchored me to my insecurities. I know from firsthand experience that the self-doubt and anxiety spiral caused by imposter syndrome can be debilitating, and those feelings have kept me from reaching my full potential before. It’s an exhausting cycle, trying to convince myself that I have earned a seat at the table, but it’s something that I’ve gotten better at over time. I’ve learned that it’s important to acknowledge negativity and anxiety as they try to worm their way into your thoughts and that it’s equally important to affirm your achievements and capabilities by believing in yourself.

Applying for the Knauss Fellowship was a crash course in overcoming imposter syndrome: I had to convince myself that my jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none background, different from my peers who had dedicated themselves to PhDs in their field of choice, made me a sufficient candidate for the program. Instead of holding myself back from applying, I acknowledged my anxiety by transforming thoughts about my perceived shortcomings into what I could learn during the experience. I affirmed my prior accomplishments by discussing what I could bring to the fellowship with my unique background. Most importantly, I got out of my own way and let my prior experiences speak for themselves.

After a few days aboard Okeanos Explorer, I took these lessons learned and reminded myself that my professionalism and training gave my mentors enough reason to presume I’d do well as a communications liaison on the expedition. Why shouldn’t I trust their judgment? It was true that I didn’t know about all of the tools we used for mapping the seafloor, but I’m familiar with terrestrial mapping and acoustics. Maybe I wasn’t an expert on bathymetry, but I’m also not an expert on artificial intelligence, and I explained that to layman audiences while I earned my master’s degree. Even lost-at-sea forest birds transfer their past experiences to life on a boat, scavenging crumbs from the deck in the absence of their preferred meal. There was no reason I couldn’t become comfortable on the ship and sufficiently perform my job.

Changing my thought process had immediate results. I started sharing what I was learning with the general public, and folks were interested in what I had to say. Not having a background in ocean exploration gave me a unique perspective on what might interest audiences. Since I was learning with the public, I could share facts or discoveries that fascinated me and that subsequently fascinated our followers. We even had media articles published about a few discoveries made during the expedition, like the true height of a giant underwater seamount. As I felt more comfortable in my job, the ship started feeling more like a home. I wasn’t getting lost trying to find my stateroom, and the crew started to recognize me as the “communications queen” and “bird nerd” of the expedition, two endearing nicknames that I accepted warmly.

Birds lost at sea have two choices: leave the ship and seek home or perish from starvation or dehydration. Luckily, my options as a landlubbing Fellow at sea were not so dire. I could wallow in anxiety or stop seeing myself as an imposter and embrace the initial discomfort of an exciting opportunity. Making the most of my position as a Knauss Fellow requires believing in my ability as a scientist and communicator, so I chose to believe in myself and my capabilities, which got me to this position in the first place. Moving forward, I will jump at once-in-a-lifetime opportunities like my time at sea on Okeanos Explorer, knowing that I am uniquely qualified and have every reason to be present.

Logan Kline

Knauss Fellow (Maine Sea Grant)

NOAA Ocean Exploration Science Communication Fellow

Learn more about Maine Sea Grant and how its work serves coastal communities in Maine and beyond.